That’s Just Your Opinion, Man

A better way to talk about subjectivity and objectivity

People love to argue. But when is it just a matter of opinion and what counts as a fact?

“That’s just your opinion, man.”

It’s a line from The Big Lebowski - a cult movie I don’t especially like, though I know that opinion puts me in the minority. And I say “opinion” deliberately, because that’s exactly the kind of thing people fight about. Not the movie itself (which exists whether I watch it or not), but how I feel about it - and whether that feeling counts.

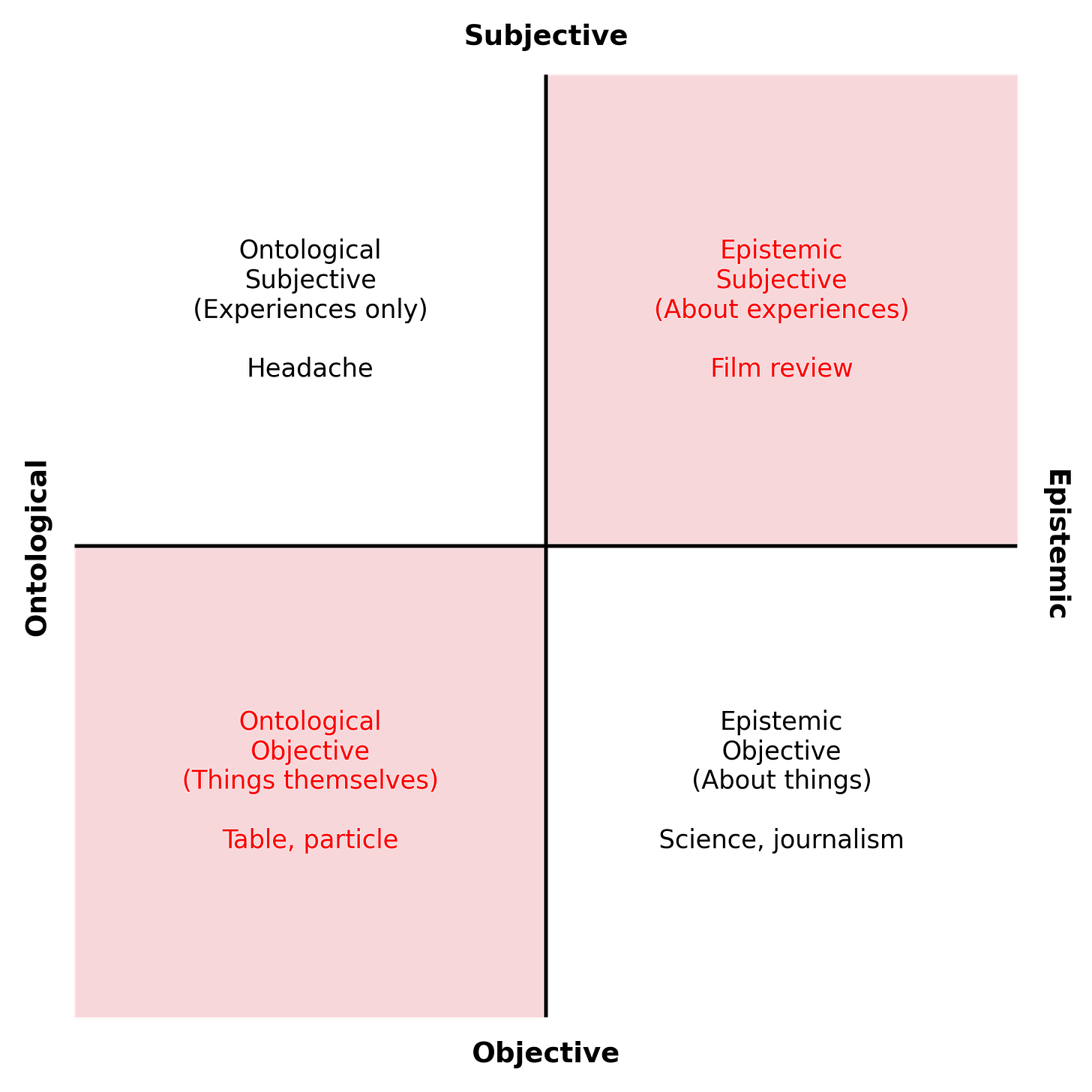

Most of us treat subjectivity and objectivity as simple opposites: opinions versus facts, feelings versus truth. But that’s not quite how it works. At the turn of the century American philosopher John Searle pointed out that we actually use the words subjective and objective in two different ways - not just to describe the content of a belief, but also the way it exists. In other words, there’s a difference between whether something is an experience or a thing, and whether its truth depends on the person saying it.

Here’s an example of each.

A headache is subjective in a deep way. If you have one, it’s real for you. But no one else can feel it. It only exists because it’s being experienced.

My opinion of The Big Lebowski is subjective in a different way. It’s about an experience (watching the film) but once I say it, it becomes something others can share, contest, or ignore.

The table in front of me is objective in the strong sense. It’s not an experience; it’s a thing made of atoms, and those atoms push back on anyone who leans against it.

An unbiased article in the New York Times is also objective - but epistemically. It’s not about anyone’s private experience, but about things in the world, carefully cross-checked so that anyone could evaluate the claim.

Searle’s point was that we need four boxes, not two:

Ontological subjectivity: things that exist only as they are experienced (a headache).

Epistemic subjectivity: statements about an experience (a film review).

Ontological objectivity: things that exist independently of us (a table, a particle).

Epistemic objectivity: statements about things, tested from all sides (science, law, journalism).

That already clears up some confusion. But I think it becomes even sharper if we focus not on abstract categories, but on the role of experience. Some things are experiences directly. Some are about experiences. Some are things that exist whether or not anyone notices them. And some are about those things - attempts to make sense of them from a shared vantage point.

This shift also helps explain why arguments get stuck. Someone says, “I felt weird in the meeting.” That’s a report of an experience. Someone else replies, “That’s not a fact.” They’re demanding a statement about things in the world. A third person says, “No one else felt that,” appealing to objectivity as events in the room. And the first person snaps back, “Well I did feel it,” grounding everything again in their brute experience.

No one is wrong. They’re just speaking across categories — mixing experiences with things, and mixing statements about them.

The practical value of this model is that it helps you stop talking past people. When someone says “that’s just your opinion,” you can pause and ask: are we talking about an experience in me, or a thing in the world? Are you asking me to change how I feel, or how I argue?

Searle’s original framing does the heavy lifting. But what makes it vivid, to me, is drawing the line through experience. Some realities live in us. Some point to our experiences. Some are out there in the world. And some are the collective work of describing those things carefully.

It’s not just philosophy. It’s a better way of listening.

Although one might argue that an objective nyt may not exist, I have nothing but praise for this kind of explication. We need more of it in such a forum as this! Way to go!

Great summary! I like the careful definitions of terms and division of categories, it definitely helps organize some of the muddy waters. A lot of the disagreements online probably come from people having different meanings in their heads behind the words they say